Ontario’s new funding formula should be providing clarity about guaranteed operating funding going forward. It should provide for significantly increased staff compensation to deal with the obvious crisis in retention and recruitment. It should give guarantees of sufficient future funding to make possible the rapid growth in not-for-profit and public facilities. It should provide spending discretion to operators to spend funds in ways that are most appropriate to their program and community. It should make clear that there will be ongoing and detailed financial accountability at the end of the funding year.

Further, the funding formula should be designed to give a key role to CMSMs and DSSABs to adjust annual funding of services to meet local priorities. And, the funding formula should ensure that child care services serving low-income, prioritized and underserved communities have the extra resources needed to serve them equitably. Otherwise, access to child care services may be monopolized by more affluent families.

However, it is not clear that any of these objectives will actually be met. Comments on the proposed funding formula can be made here until May 5th 2023.

What’s Wrong or Unclear About the Proposed Formula

- It would be preferable to base the funding formula on its outputs rather than on its inputs. In other words, the funding should be based on a target per diem for projected annual enrollment of infants, toddlers, preschoolers, kindergarten children etc., with funding adjustments for facilities with extra costs and unusual situations. The proposed funding formula, which is based on inputs, is excessively bureaucratic and does not give much discretion to operators about how best to spend money to achieve desired goals in their circumstances. Hopefully, this current proposed funding formula is a step along the road towards a better design. However, a better funding formula based on a target per diem requires that wage rates and other compensation are reasonably uniform across all operators – that means that operators are paying staff according to a wage grid. This is where the future of the funding formula should lie.

- It is unclear what the meaning of “average base wage rate” is for RECEs and non-RECEs. Is this some kind of average across the CMSM/DSSAB? That would not make any sense; for many operators, it would not even cover current costs. Instead, it seems to be the facility-specific current average wage before any wage supplements as reported on the most recent child care operator survey.

- The first problem is that these average wages have not generally been reported on the child care operator survey. Instead numbers of staff in different wage ranges are reported. The new operator survey with responses due in early May has narrower wage ranges for reporting. Is this going to be used to calculate average wages? In any case the average wage should be taken only across staff providing care for children 0-5, and this is probably not the case on the most recent operator survey. And the average wage should be calculated as a weighted average wage for RECE staff with the weights being the different number of hours worked by different staff. That would be more appropriate than a simple average, but the proposed funding formula ignores this.

- The second problem is that there are clearly very significant retention and recruitment issues at prevailing wage and benefit rates. Average wage rates for ECEs in Newfoundland and Labrador will be considerably higher than in Ontario for the foreseeable future! This is ridiculous and unsustainable, as the cost of living is much higher in Ontario. The funding formula should be based on a target wage grid at considerably higher wages than currently and operators should be invited to calculate compensation costs based on this wage grid.

- The program staffing grant funding formula is based on 260 days rather than 261. In fact, 2024 will have 262 days of operation.

- The staffing grant is not based on the expected number of hours worked but on the expected number of hours and days that the centre will be open. This is an issue for kindergarten children where the formula seems to assume full-year attendance though many children of this age do not actually attend during summer hours and days. In general, the government’s proposed formula will advantage centres where children attend less than full-time hours because the formula will pay for the number of staff required as if the child was present for all hours the centre is open.

- The annual wage cost increase is part of the formula but has not been specified. This should be inflation plus some percentage. Of course, some collective agreements and other commitments made by School Boards will already specify an annual increase that needs to be respected.

- The program staffing grant formula is based on the percentage of program staff who are RECEs and the percent that are not RECEs. Instead, it should be based on the percent of the projected number of hours worked by RECEs and by non-RECEs, not the simple numbers of staff of each kind. Variations in staffing costs are based on hours worked, not just the numbers of staff hired.

- Are director’s approvals staff working in RECE positions considered to be RECEs for wage calculation purposes? Is this an incentive for operators to seek director’s approvals in future hiring?

- The program staffing grant does not include any allowance for training and professional development, or covering absences for professional development. It is important to provide strong incentives in the funding formula towards increased and regular professional development.

- The program staffing grant does not make any explicit allowance for planning time for RECEs and staff meeting time.

- Only one FTE supervisor is allowed (e.g., for 7.5 hours per day) and no assistant supervisor. This does not account for all the hours a centre is open in a day, let alone the need for more supervisory staff in larger centres.

- There is no allocation for pedagogues that are above required ratios.

- The supervisor’s wage appears to be based on some kind of average across centres in a previous survey, rather than the past wage or necessary future wage received by the supervisor in this centre. In the future, there will need to be a salary scale for supervisory staff.

- The accommodation grant formula is based on gross floor area. Does this include playground space?

- How will this accommodation formula take into account capital renewal and capital maintenance? Will the typical rental rate be based on new facilities, old facilities or what?

- The accommodation (i.e., occupancy cost) formula should distinguish between for-profit and not-for-profit auspices. For-profits may own their own building or may have an non-arms-length interest in the value of the property. Accommodation funding may increase the value of their real estate in private hands. Not-for-profits do not accrue these increases In value because their assets stay in public hands. This suggests there should be very tight rules on accommodation grants for for-profits that have any financial interest in their premises, and looser rules on accommodation grants for not-for-profits.

- There does not appear to be any recognition of the considerably larger costs going forward that are due to administration and reporting requirements. This should be an explicit part of the operating grant.

- The funding formula is silent on what will happen to future funding for children whose families receive child care subsidy. This is a big problem. There is no explicit commitment in the funding formula about the amount and distribution of money or number of families who will benefit from child care subsidies directed at low-income families and families otherwise in need. We know that as the parent fee for licensed services is lowered, a larger and larger percentage of available spaces will be taken by families whose incomes are above subsidy-eligible levels. We also know that providing high quality care for subsidized children may take extra staff time and result in higher costs. If the funding formula does not reward centres who take subsidized children with extra funding, subsidized children will tend to get squeezed out. It may also be necessary to take other measures, such as reserving spaces for subsidized children, to ensure that children receiving child care subsidies and other prioritized children are at the front of the line for available spaces.

- The proposed funding formula makes CMSMs and DSSABs into flow-through agencies for the distribution of funds, rather than service system managers. Previously, CMSMs and DSSABs have played a key role in defining and funding local child care priorities. The new funding formula should restore some of this local funding discretion, allowing municipalities with long subsidy waiting lists to direct more funding to these families, allowing other municipalities to direct more funding to children with special needs, to centres serving Indigenous children, to centres increasing accessibility for rural families, etc.

Principles Upon Which the Funding Formula Should Be Based

The funding formula should:

- cover all the legitimate operating costs of a centre providing quality licensed child care services at or above regulatory minimums for children 0-5 across Ontario;

- cover compensation costs for Registered Early Childhood Educators and assistants at wage and benefit rates that are competitive with other occupations requiring similar education, training and practicum requirements such that early learning and child care in Ontario is not characterized by staff shortages and widespread director’s approvals;

- reward and encourage ongoing professional development and increased educational qualifications of both early childhood educators and assistants;

- provide for extra compensation for early childhood educators with special qualifications such as special needs qualifications and pedagogue qualifications;

- give operators discretion in decisions about the expenditure of allocated funds (ability to transfer funds across grant categories), but also require operators to report in detail at year-end about how funding has been spent, and adjust funding amounts as necessary;

- adopt a desired wage grid and, perhaps, a timeline over which to achieve it. The funding formula should reward operators who pay wages and benefits according to the timeline of recommended wage and benefit rates;

- recognize sources of additional legitimate costs, such as providing care to a large number of children with special needs, even if not diagnosed, or caring for a large number of subsidized children living in disadvantaged circumstances or providing extended hours of care;

- recognize higher costs per child that come from operating a small centre in a rural or remote area;

- distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate reasons for having higher than normal occupancy costs;

- encourage expansion, especially within existing facilities. So, for instance, the formula should be based on either licensed capacity or the expected number of enrolled spaces over the next year as opposed to past enrollment (i.e., past operating capacity).

General Comments on the Funding Formula

The agreement signed between Ontario and Canada sets Ontario on the path to charging approximately $10 a day for licensed child care by 2025-26. For those operators who have chosen to become part of the CWELCC system, fees charged to parents are already more than 50% lower than the fees charged on March 28th, 2022 when Ontario signed the agreement. It is likely that all providers will charge a regular parent fee of $12 per day in 2025-26. Because the fees for children in low-income subsidized families will be at or close to zero, the average parent fee across the province will average $10 per day.

The agreement moves licensed child care in Ontario towards a public service largely funded by government, so that it is affordable to families. Over time, the amount of licensed child care for children 0-5 in Ontario will expand, so that the service is essentially universal. However, right now, there are supply shortages of all types of care in all parts of the province.

The purpose of a funding formula is to determine the amount of funding needed by each participating operator in each facility to cover the reasonable costs of providing child care services to children 0-5. These services will include full-day and part-day care for infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and children of kindergarten age. There will be some services that are open for non-standard hours or perhaps even overnight. There will be special support for children with special needs. There will be some centres that offer a forest school experience or services that are enriched in other ways.

There are two components of the cost of providing child care that are highly variable across operators – costs of compensating staff and accommodation costs.

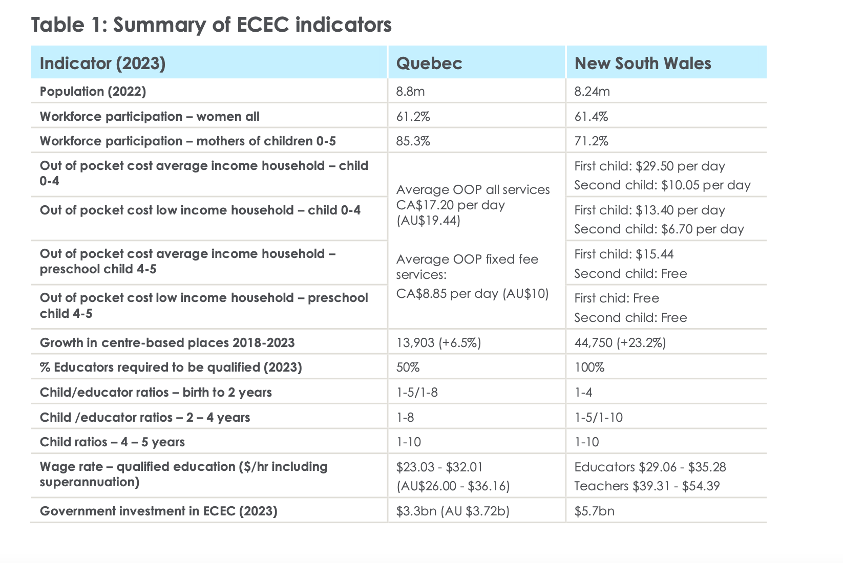

In other jurisdictions that have wage grids, either bargained by unions or through an awards system or by government fiat, compensation levels are more similar across different providers. This makes it easier to, for instance, work out the approximate variation in costs of providing care for infants, toddlers, preschoolers etc. If there is a wage grid, as in Quebec, a funding formula will be based on the services delivered, with a standard amount of funding for each unit of service. In Quebec, the largest component of the funding formula is based on projected enrollment in spaces for each age category. There are adjustments to these gross amounts to take account of higher costs in centres with higher wage and benefit levels, differences in enrollment and attendance, etc.

Ontario does not have a wage grid that defines expected wage and benefit levels and it has not historically collected information about legitimate variations in costs across providers. As a result, Ontario has chosen to design a funding formula based on expected or current staffing costs, rather than on the amount and detail of services provided. The 2024 Funding Formula Discussion Paper indicates that there will be four separate grants relevant to the costs of child care centres:

- The program staffing grant

- The program leadership grant

- The operations grant

- The accommodations grant

In addition there will be a home child care grant and a grant to cover the administration costs of service system managers.

All of these grants refer only to CWELCC services for children 0-5 in facilities that have become part of CWELCC. They will not fund services to children 6-12 or the staff that care for them. They do not explicitly cover the financing of child care subsidies and there is no commitment in the funding formula to maintain and expand the number of children who receive additional subsidized assistance with child care costs. They do not cover funding of facilities that have not joined CWELCC. All of the existing grants including wage enhancement and other grants for services covering children 0-5 are rolled into the new funding formula and disappear as separate grants.

The new funding formula will have to cover staffing costs, operating costs and occupancy costs for child care facilities across the province in very different situations. The funding formula is not intended to cover capital costs of expansion or start-up costs. However, the funding formula is intended to provide a guarantee of future funding amounts upon which a child care facility’s decisions about expansion will depend.

The funding formula paper is supposedly a formula for determining the amount of funding that will be allocated to each CMSM/DSSAB. However, the funding directed to CMSMs and DSSABs is based on the aggregation of the amounts of funding that facilities in the CMSM or DSSAB will get. So the funding formula apparently determines funding both at the level of the individual facility and of the CMSM/DSSAB.

The Ministry sponsored a mini-survey of child care costs designed to help calculate amounts needed to cover the costs of each facility. The degree of detail on costs collected is insufficient to fill holes in the funding formula. However, the funding formula paper says that this mini-survey is “foundational to building this cost-based model” and that “Those cost structures, including their variability, are captured through weighted averages and benchmarks at the CMSM and DSSAB level in the funding formula.” In apparent contradiction to this talk about data at the CMSM and DSSAB level, the document also says that “Funding from CMSMs and DSSABs to licensees would consider the cost structure of each individual licensee and, since the formula captures high and low cost structures, the funding allocations would support the financial viability of licensees.” Greater clarity is needed about these apparent conflicts in description.

The formula for the Program Staffing Grant is described in simple terms as “multiplying the number of program staff working hours by the compensation cost per hour, and adding a supply staffing allocation (for coverage during absences). This calculation would be done at the child care centre level and then aggregated to derive the program staffing grant amount for each CMSM/DSSAB….”

The actual formula looks somewhat different to this simple description, however.

Instead of actual hours worked by staff, the formula calculates the number of staff that should be required (according to legislated child-staff ratios) times the number of hours the centre would be open if it were open every day of a 260 day year. That means if a centre is “over-staffed”, the extra staff is not included in the funding formula. If the centre is located in a particularly disadvantaged area or has children with substantial extra needs, you can easily imagine a centre being staffed above the ratios. This might be an issue in rural areas with small centres where the required number of staff is fractional. The formula does not account for this.

The formula presumes that all children attend the centre for the full number of hours it is open each day (e.g., 11 hours per day), rather than some arriving after opening and some leaving before closing. It is presumed that the total number of operating days per year is 260 (rather than 261 or 262). And it assumes that the daily staffing costs do not vary on statutory holidays, when the centre may be closed, which could be an issue especially for workplace-based extended-hours care. Further, the formula is based on “operating capacity”. The glossary defines operating capacity as “the number of children the centre/home child care is planning to serve as per the licensee’s staffing complement and budget, to a maximum ceiling of the licensed capacity.” In other words, it is the capacity that the centre is staffed for. Operating capacity is an intention or plan. It is not clear how operating capacity is related to enrolment. The actual costs of staffing are likely to be closely related to enrolment.

This calculation of the number of hours of staffing required (which is calculated separately for different age categories with special complications for children of kindergarten age), is then multiplied by a composite average compensation amount per hour. This average compensation amount per hour is calculated as the sum of (a) average wage plus benefits of RECE program staff in the centre times the percent of staff that are RECE and (b) the average wage plus benefits of non-RECE program staff in the centre times the percent of staff that are non-RECE.

This calculation of the average program staff compensation per hour has many problems. First, it is said to be based on average wage information from the most recent child care operator survey. However, the annual operator survey in Ontario does not collect information about average wages; instead it collects information about the numbers of staff whose hourly wage is in different ranges (e.g., $17.50 to $20.00 per hour). The mini-survey did not collect this information either. So, there is apparently no accurate basis for calculating the average wage or average compensation in a centre from existing provincial data.

Second, it is based on the percent of RECEs and non-RECEs in the centre. It should be based on the number of hours worked by RECEs and hours worked by non-RECEs. And, as long as there are going to be presumed RECEs based on Director’s Approvals that generally earn less per hour than RECE’s, there probably should be three categories of average compensation levels. And, there does not appear to be any recognition of the need for specialized staff, whether they be related to children with special needs or whether they be pedagogues supporting other staff. Where does the compensation of these staff fit in? And where does planning time fit in?

Calculating the average compensation per hour for different groups will not be trivial. The hourly base wage for each staff member (presumably this means the actual wage directly paid by the operator to each staff member) may be reasonably straightforward if staff are hourly paid, but a little less straightforward for staff earning a salary. On top of this needs to be layered the various wage enhancement grant amounts whether part of CWELCC or from before. Then there will be an annual wage cost increase allowed. Plus the cost of benefits. And all of this has to be stated as an average per hour compensation amount for each program staff and then this hourly amount will be averaged over all the RECE staff and the non-RECE staff separately. The cost of many benefits does not necessarily vary directly with hours worked, so that can be a problem.

And then there is an allocation for supply staff, based on a benchmark somehow calculated. What about coverage for staff who go on maternity/parental leave, or disability leave, and top-ups paid for these leaves in some centres? How does a general benchmark cover this?

There is no discussion in the formula about how to handle rising wage costs over the course of the year, presumably related to the rising wages that need to be paid to recruit new staff. This will be a real problem if expansion is to occur.

In general, it is unclear how new centres will be funded. There is no existing base of wage information for these centres on which to base staffing grants. Their wages and costs are likely to be higher than other centres because (a) they have to recruit staff in a situation of labour shortage and (b) many new centres are located in underserved communities where per-child costs may be high. How can expansion happen if there is no clarity about future funding guarantees?

Amongst other things, It is obvious that the province should have been collecting much more detailed financial data from operators before trying to design a funding formula. It will need to ensure the collection of detailed financial data going forward in order to make changes to the funding formula over time.

Gordon Cleveland

April 21st, 2023