Many Canadians do not seem to realize that funding child care with tax credits would mean having no control over child care fees. Plus, there would be no financial accountability by operators for the public money they receive. Right now, child care fees are controlled in Canada – in eight of Canada’s thirteen jurisdictions, the fee is $10 a day. By April 2026, parent fees will be limited to $10 a day across the country. If we switched to tax credits (as the Conservative Party recommended in the last election), there would be no limitation on parent fees and no financial accountability for billions of dollars of public money. Child care operators could charge whatever the market would bear. And so, for many families, child care would be unaffordable once again.

I’m in Australia right now. It’s a gorgeous, sunny country with great restaurants, stimulating and dependable coffee, and very friendly people. But they have problems with their child care system that we can learn from.

You can give money to parents to fund their spending on child care; mostly, that’s what Australia does. Or you can fund the services to ensure that they will be available and affordable; mostly, that’s what Canada now does. The first is called demand-side funding. The second is called supply-side funding.

Demand-side funding comes under different names – a tax credit or a voucher or a parent subsidy; it amounts to the same thing. Australia has a Child Care Subsidy; there are bigger subsidies for low-income families and smaller subsidies for high-income families. The payments are made to the family’s chosen child care provider (from amongst approved child care providers), based on the amount of child care used. The parents have to pay whatever child care fees are not covered by the subsidy.

Australia has a market-based child care system. There are standard regulations on employee qualifications, staff-child ratios, health and safety, and so on. But, there are no effective government controls on the fees that are charged by providers and centres can be established wherever they choose – usually where it is most profitable. The majority of providers in the system are for-profit corporations and entrepreneurs.

Australia gives Canadians a chance to see how demand-side funding works in practice. And, I would argue, Australia gives a “best case” scenario for this approach. Australians have tried very hard over the years to make this subsidy/tax credit approach work equitably and efficiently for all families and they have done a lot to promote higher quality in child care services. I would argue that if Australia can’t make a demand-side funding system work effectively to make child care affordable, accessible and of high quality, then no one can.

In this context, the November 2024 report by Dr. Angela Jackson, Lead Economist for Impact Economics and Policy is well worth a read. The report – Time to Stop Throwing Good Money After Bad – was commissioned by the Minderoo Foundation, a charitable organization founded by Dr. Andrew Forrest (former CEO of the Fortescue Metals Group) and Nicola Forrest. The report provides an assessment of Australia’s child care funding and management system.

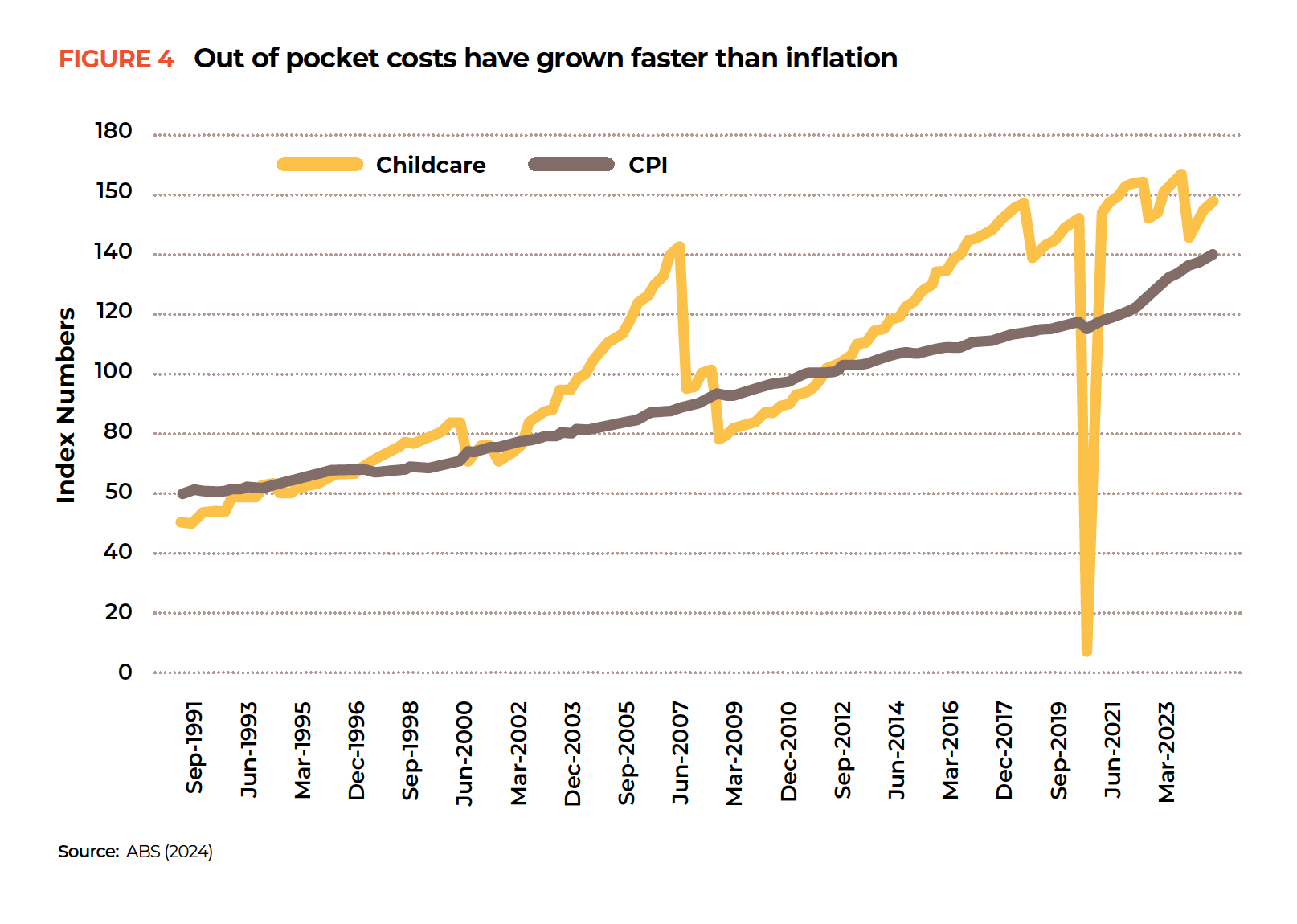

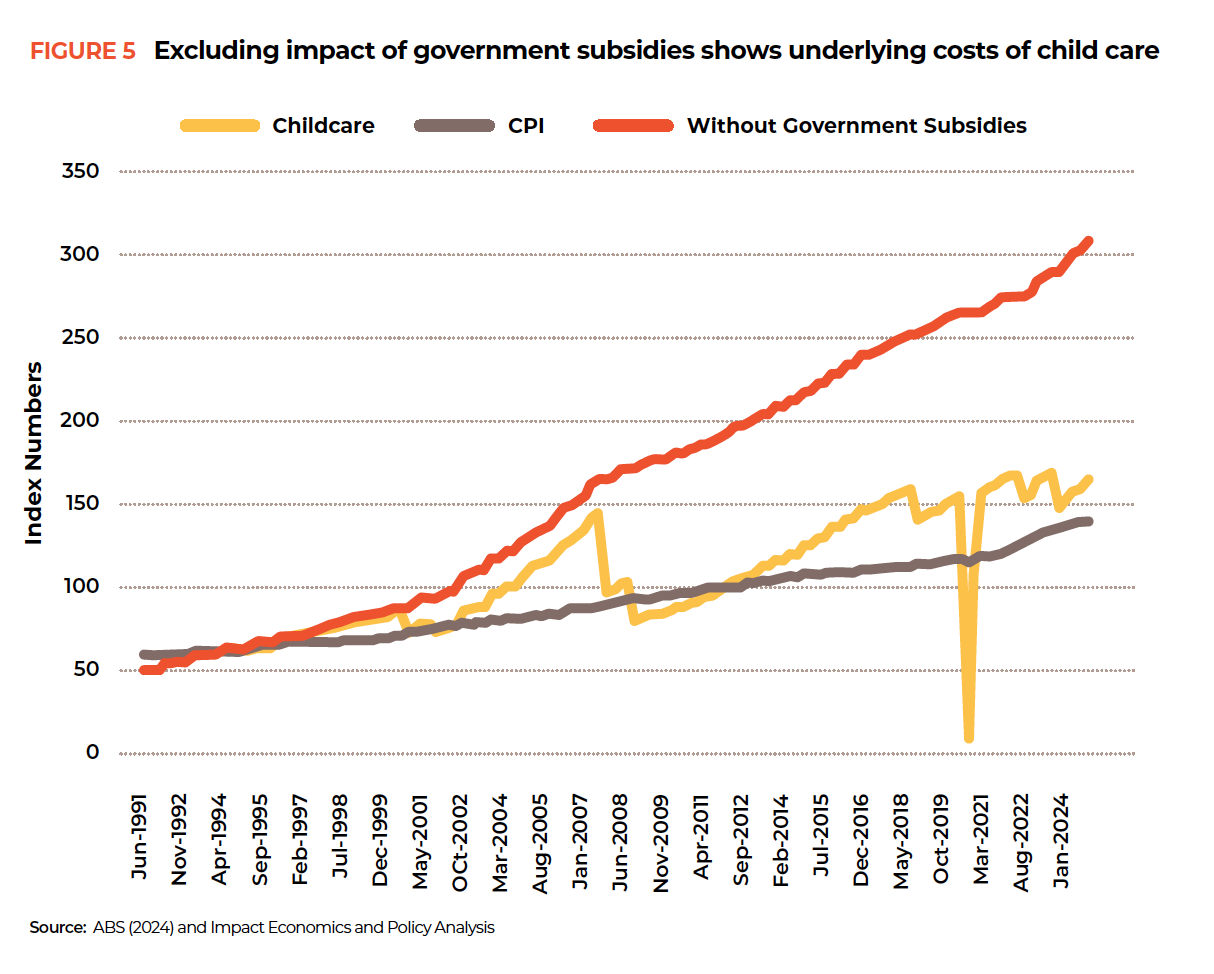

I think the best place to start is to look at two charts that Dr. Jackson features in the report.

Figures 4 and 5 are copied from her report. Figure 4 covers the period from 1991 until 2023. What you see are two lines. One is relatively straight, showing how the Consumer Price Index has risen pretty steadily over this period of 32 years. The fiscal year 2011-12 is the base year and gets an index value of 100. Compared to that, the average price level in the economy has risen from 50 back in 1991 to 140 now.

The second (yellow) line is very jagged. It goes up, then falls, then rises rapidly, then falls. Again and again. This line shows the “out of pocket costs” of child care. Out of pocket costs are the amounts that parents actually pay for child care after accounting for the child care subsidy they receive. When government increases the subsidy, the out of pocket costs go down. When fees charged by child care operators rise but the subsidy stays the same, then out of pocket costs rise.

In the battle between rising child care fees and increasing levels of subsidy, child care fees have been winning. Overall, the amounts paid by parents have been rising faster than inflation despite subsidy increases.

In Australia, there were major infusions of funding and reform of child care policy in 2000, 2007, 2008, 2018 and 2023. In 2020, during the pandemic, child care services became free for those continuing to use them. We can see each of these events on the chart as a sudden drop in the yellow line.

But none of these funding infusions have stopped the upward march of child care fees. Out of pocket costs of child care have increased quite a bit faster than inflation over this 32 year period DESPITE many government attempts to improve tax credit/parent subsidy funding arrangements to make child care more affordable. Child care has become, on balance, less affordable, not more affordable. In 2023, after Child Care Subsidy is accounted for, the average out of pocket cost of child care for parents in Australia was $44.42 per day (or over $11,500 per full year).

By how much have child care fees risen over this time period? Figure 5 provides this information. It includes the two lines from the previous figure but adds a new one. This third (red) line, rising above the other two shows the amount by which the cost of child care to parents would have risen had there been no improvements in child care subsidization. The underlying costs of child care have risen by 499.9% over this period – much much faster than the rise in consumer prices! In 2023, before subsidy, the average child care fee for full-day care in Australia was $133.96 (or nearly $35,000 for a full year).

This pattern continues to this day. As Dr. Jackson notes, over the last 12 months child care fees have increased by 10.6%, which has eroded the benefits of the new $5 billion child care expenditure program begun in July 2023.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, which held an inquiry into costs and prices of child care providers in 2023, described this repeating pattern accurately:

“when government subsidies increase, out of pocket expenses decline sharply in the immediate term, but then quickly revert to levels preceding the subsidy change.”

Is this pattern a glitch? Or is it a feature that we should expect to observe if Canada were to adopt a tax credit system for funding child care? Those who support tax credits emphasize parent choice and flexibility. What they do not tell you is that tax credit systems mean that there is NO CONTROL over the fees charged by child care providers. There is no regulation of the decisions that corporations and entrepreneurs make about where to locate their services. And further, there is no requirement that child care providers account for the ways in which they spend the billions of dollars of government money they will be receiving when subsidized children attend their facilities.

With a tax credit system, additional government spending largely benefits providers, not families. True enough, this very generous funding system has encouraged providers to expand. There were enough centre-based spaces for only 7% of Australia’s children 0-4 years of age back in 1991 and there is now coverage for 42% in 2022.

Since there is little control over where providers locate, access to child care is concentrated in wealthier areas where providers can charge higher fees. 24% of Australia’s households with children are located in child care deserts.

The large majority of providers in Australia are for-profit enterprises. And for-profit providers have been found, in Australia as elsewhere around the world, to provide lower quality child care on average. Australia has put a lot of resources into measuring quality of services. Their quality rating system has five result categories: Significant Improvement Required, Working Towards National Quality Standard (NQS), Meeting NQS, Exceeding NQS, and Excellent. 35.4% of not-for-profit providers are rated as Exceeding NQS or Excellent. Only 12% of for-profit providers reach the same levels. Further, for-profit providers have been found to be half as likely to increase their quality ratings over time as the not-for-providers are.

Viewing the Australian experience with a Canadian lens, the tax credit approach has many weaknesses. In a tax credit system, the only way to make child care affordable for parents is through substantial infusions of government funding. However, if substantial government funding is combined with providers having the freedom to set and change their own fee levels, then the result will be rapidly rising fee levels and reduced affordability. On top of that, there is no requirement for child care operators to account for how public money is spent.

In theory, competition among providers is supposed to bring fees down and force providers to offer better quality of care. In practice, competition is very imperfect, partly because child care markets are very localized, so few providers compete directly with each other. Competition is also imperfect because parents can only perceive and evaluate child care quality imperfectly.

So a tax credit or voucher system pushes up child care costs, profits and fees but delivers child care that is expensive for governments, unaffordable for many families and very uneven in quality. Governments get into a cycle of additional spending to bring out of pocket costs down, then watching as provider fees rise to make child care unaffordable once again. Whatever its growing pains, $10 a day child care is a much better bet than tax credits to provide affordable, accessible, quality child care.

*********************************************************************************

| However, Supplementary Subsidy Funding Plays A Positive Role Most Canadian provinces and territories have child care subsidy systems that are supplementary to their main way of funding child care. The effect of this is positive. The main funding is on the supply side – funding to operators in exchange for child care services made available to families. On top of that, most provinces and territories have a subsidy system that can lower the parent fee from $10 a day (or, currently, a higher fee in five Canadian jurisdictions) for low-income or multiple-child families that cannot afford $10 a day. Most of these subsidy systems are imperfect, but they serve the very important purpose of ensuring affordability for all families, even those who cannot afford current reduced fees. |