Todd Smith is Ontario’s new Minister of Education and he has already decided who he wants to blame for Ontario’s child care shortages – it’s the federal government. So, Todd Smith wants federal minister Jenna Sudds to release Ontario from the agreement it signed back in 2022 that limits expansion by for-profit enterprises to a maximum of 30% of the total expansion. Ontario never wanted to limit for-profit expansion; apparently they only signed the agreement under duress.

The problem of child care shortages is a real one. We need a lot more child care expansion in Ontario and we need it now. We will need even more child care when Ontario drops the parent fee down to $10 a day.

But Todd Smith doesn’t seem to understand why Ontario is facing such a shortage of child care spaces, so he’s coming up with solutions that are antithetical to the high quality universal child care we have been promised. He’s new in his job, so let’s give him a primer:

- Ontario knew very well that there would be a huge shortage of child care spaces. The Financial Accountability Office of Ontario told them this in November 2022;

- The solutions are well known. Ontario’s officials and politicians were told by many people – including me and the Financial Accountability Office – what steps they needed to take to make child care expansion happen;

- Instead of implementing these solutions, Ontario has fumbled and delayed and prevaricated and done nothing, or very little, to facilitate the child care expansion that is needed;

- Now, Ontario wants to blame the federal government for Ontario’s failures to provide new child care facilities for parents and children that need it. Some blame is due to the federal government, but Ontario is the one with the responsibility and capacity to fix the shortages;

- It is true that for-profit child care providers are quicker to assemble capital funding than non-profits, but there are serious long-term costs. Ontario knows well how to facilitate non-profit and public child care expansion; its current child care system has been built primarily this way.

- Quebec’s experience makes it clear that relying on for-profit child care can come at a substantial cost in child care quality, which Todd Smith is ignoring.

Ontario knew there would be a substantial shortage of spaces

In November 2022, the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO) reported to the Legislative Assembly that at $10 a day, Ontario parents would need 300,000 additional child care spaces. Demand would increase by that much. They compared that to the 71,000 additional spaces that Ontario was planning to add between 2022 and 2026. The FAO’s conclusion was that when parent fees reach $10 a day “…the families of 227,146 children under age six (25 per cent of the projected under age six population of 919,866 children in 2026) would be left wanting but unable to access $10-a-day child care.”

I had published similar estimates in May 2021.

Ontario has promised an additional 86,000 new child-care spaces compared to 2019. As Allison Jones article for Canadian Press tells us, so far there have been about 51,000 new spaces created in Ontario, with only half inside the $10-a-day system.

Ontario knew what to do to expand child care

The FAO, in its understated way, had already identified one key barrier to expansion that Ontario should deal with. Its November 2022 report stated that “…uncertainties over some aspects of the $10-a-day child care program, such as the extent of ministry reimbursement of future cost increases to child care providers, could reduce incentives for child care providers to create spaces.” In other words, if child care providers do not know whether revenues will be enough to cover their legitimate costs, they won’t decide to expand.

Working with Building Blocks for Child Care (B2C2), I wrote and circulated widely a paper and a blog post laying out the steps needed to facilitate the expansion of non-profit and public child care:

- A system of capital grants and loan guarantees for not-for-profit and public operators

- Creating public planning mechanisms with provincial, municipal, school board and community members

- An inventory of publicly-owned lands and buildings suitable for child care expansion

- Mandate where possible the co-location of licensed child care services whenever business and housing developments happen

- Explore the use of Land Trusts to preserve the preservation of child care assets in public hands for future generations

- Use provincial legislation and regulations to control transfers of child care assets and ensure they are not controlled by big-box corporate child care chains

- Early guarantees of operational funding and licensing of not-for-profit and public operators that plan expansion following public plans.

- Development and implementation of a province-wide salary and benefits grid and much more funding to increase compensation of educators and other staff. Recruitment and retention of qualified educators is Job #1.

- Transparent and effective future funding guidelines to support expansion. Assistance to municipalities to implement financial accountability measures in a long-term funding model.

- Public funding of organizations such as B2C2 that support not-for-profit operators to negotiate hurdles associated with expansion of child care services

Ontario has done very little to facilitate expansion

Ontario thought that child care expansion would be a natural process, not requiring much government support. Based on what Ministry of Education officials told the FAO “The ministry plans to create 71,000 net new spaces through what it terms natural growth (48,459 spaces) and induced demand (22,406 spaces)” (FAO Report, 2022). Except the “natural growth” has not happened. Here’s why.

In Ontario:

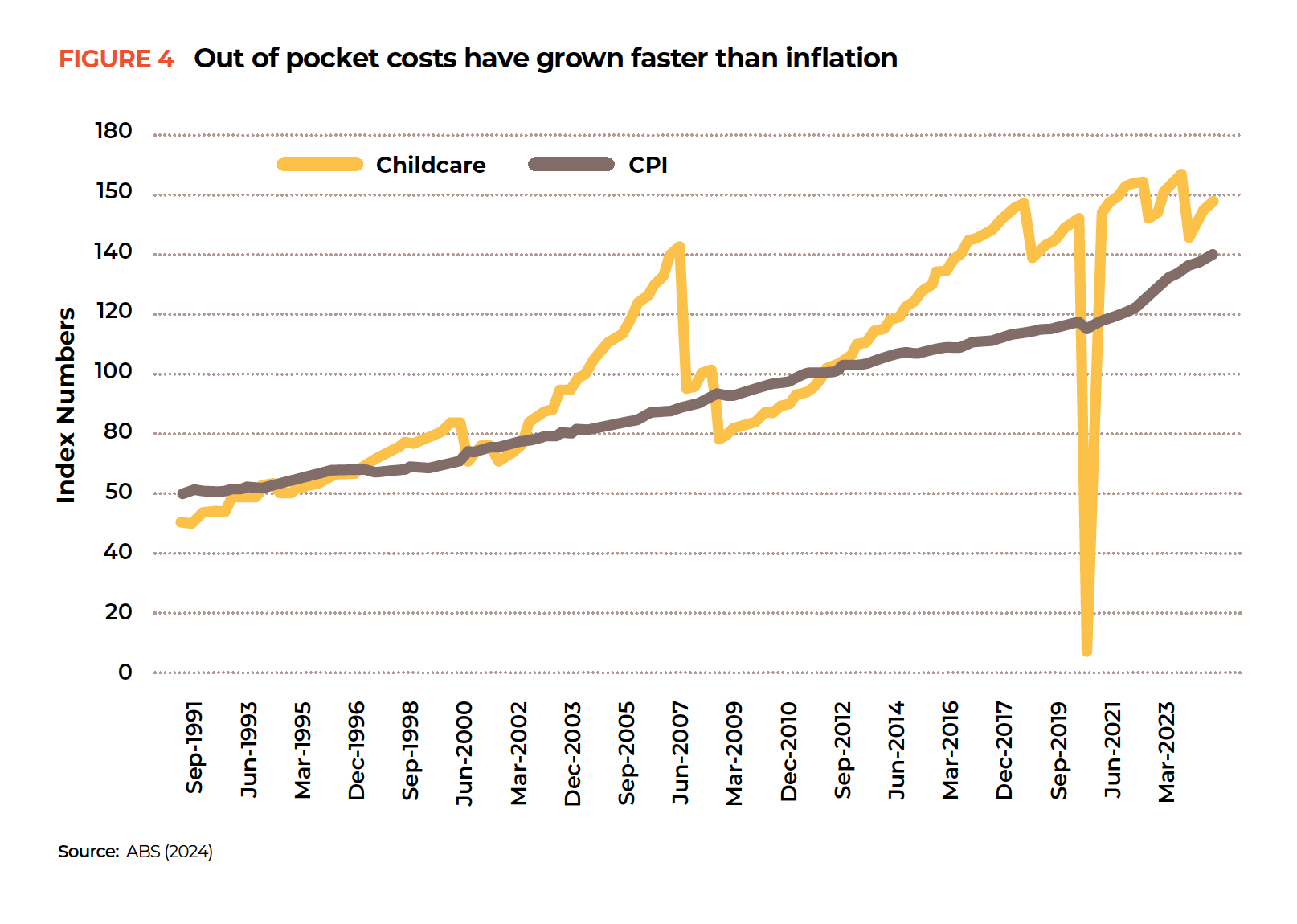

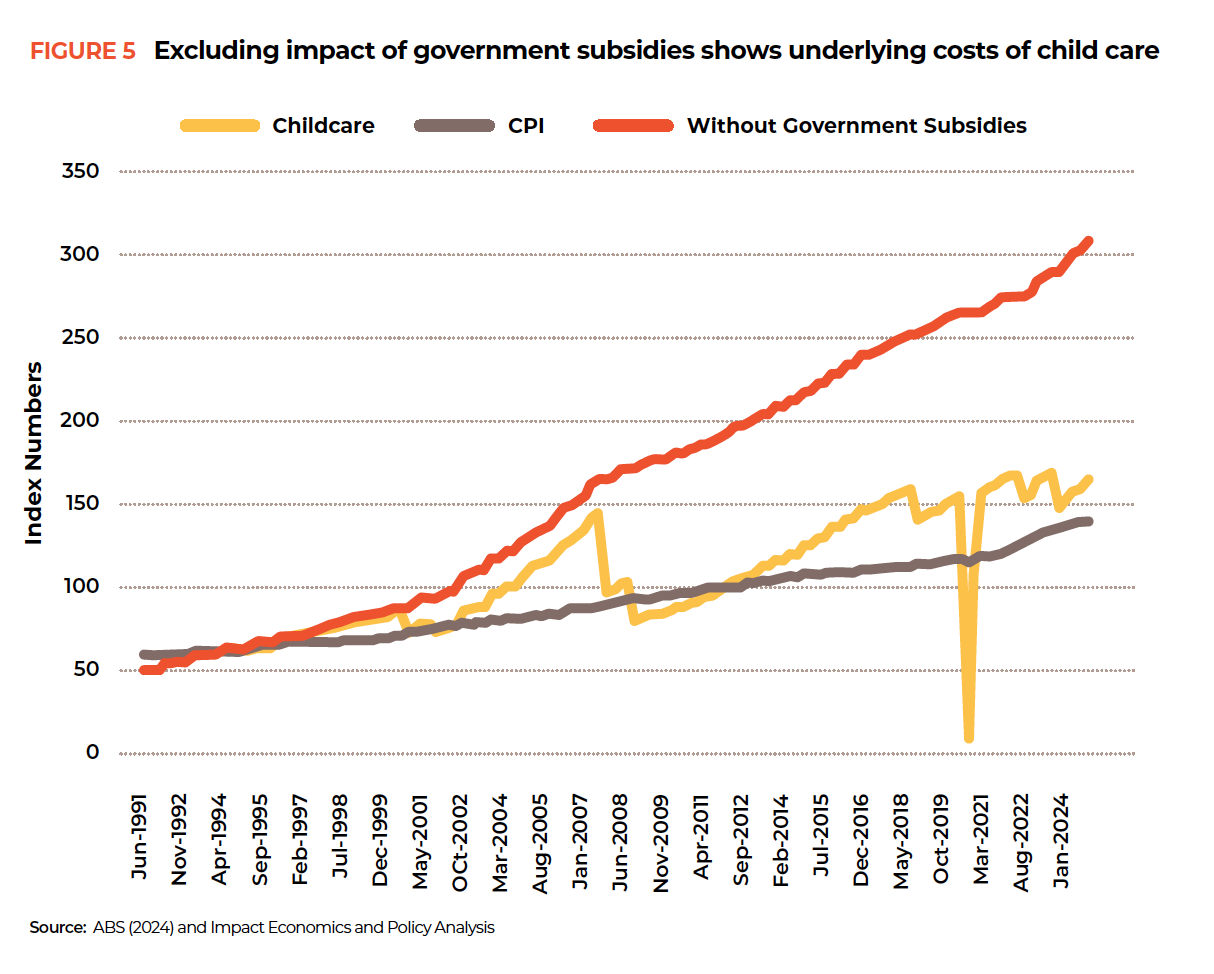

- Operators do not know what their future revenues will be or what factors will generate more or less revenue. Their future revenues will be governed by the new funding system which Ontario promised in 2023 and again in 2024 and now will come in 2025. Ontario still has the funding arrangement it invented on-the-fly on day one of the new child care system. Which was to just replace the exact amount of the fee that child care centres charged on March 27, 2022. But as anyone who has lived through the last few years would tell you, the costs of everything have been changing a lot in the last while. And since, in the child care sector, there are substantial shortages, costs of some things have been rising substantially.

- There is very little funding support for expansion of child care centres. There is start-up funding to pay for toys and equipment, but no capital grant program for community child care. There has been capital money for new centres on school board premises, first announced in 2019 (i.e., expansion planned before the $10 a day program), but now even expansion in 56 of these school board centres has been cancelled by the Ontario government.

- In the midst of a huge shortage of early childhood educators – estimated by the Ministry of Education as a shortage of 8,500 new educators by 2026 – the support by the Ontario Government for staff wages is stingy at best. In Ontario the base wage rate for an early childhood educator is $23.86 per hour, while the average hourly wage of all Ontario employees is $36.14 per hour. In PEI, the base wage rate for an early childhood educator is $28.36 per hour, and the average hourly wage of all PEI employees is the same – $28.36 per hour. There are huge child care staff shortages in Ontario, but not in PEI.

We know that Ontario is able to expand capacity quickly if it were to be a priority. In 2010-2014, Ontario provided expanded classroom space for about 280,000 children who moved from half-day kindergarten to full-day kindergarten. All of that expansion in only 5 years. Because it was a priority. The financial and personnel resources were mobilized to make it happen. But, the expansion of child care for the tens of thousands of Ontario children who want access is clearly not a priority for this government.

Having committed itself to building an affordable, accessible child care system largely with federal money, the Ontario government decided to sit on its hands and let the system fall apart. They did the easy part. They lowered parent fees, initially by 25% and then approximately by another 25%, so that parent fees are much lower than they were. So, demand for child care has skyrocketed.

But the Ontario government has not done the hard parts – reducing workforce shortages by raising compensation, providing substantial capital and management supports for child care expansion, and implementing a funding system to provide guaranteed operating revenues for providers.

So, now there are shortages. And the Ford government has been sitting on its hands, waiting for the crisis to get worse.

Ontario wants to blame the federal government

This was a sweet deal for Ontario, because the federal government committed to turning over a huge whack of money to Ontario to make this happen. In the first year (which was virtually over by the time Ontario had signed the agreement), the federal government provided $1.1 billion for Ontario child care. In every year after that the federal contribution to child care in Ontario has risen and will reach just less than $3 billion in 2025-26. By this time, the federal government will be paying about $3 for every $2 spent by Ontario to support providing child care for Ontario’s children and families.

There are elements of blame that the federal government should wear. The reforms should have been phased in more slowly, so that demand did not ramp up so fast. And, the federal government will need to provide more money – there is not enough to support child care for an additional 300,000 children that the FAO predicts will want child care.

But the federal government has now put over $1 billion on the table in reduced-interest loans and another $625 million distributed to provinces for capital grants to support child care expansion. Ontario will get the largest share of those amounts.

If Ontario does not do the hard work of…

- reducing workforce shortages,

- providing supports for child care expansion by nonprofits and public agencies, and

- providing operating revenues with an equitable and sufficient funding system,

then sufficient child care expansion will not happen in either the for-profit or the non-profit and public sectors.

For-profit expansion is easier but more dangerous

When it comes to growth, for-profit child care providers have structural advantages over not-for-profits. Not-for-profits are frequently unwilling to go into debt, so there needs to be a program of capital grants and encouragement to access low-interest loans to pay for the costs of building new facilities or repurposing existing buildings.

The mission of for-profit businesses is to make a profit, so expansion is a natural fit, particularly when the government is paying 80%-90% of the operating costs and providing a guaranteed demand for services. Shareholders or banks are always willing to ante up when the government is willing to provide guaranteed funding for profit-making businesses. They are not used to providing similar supports for non-profits in the child care sector.

But there are ways around these structural barriers faced by not-for-profits. Not-for-profits need two main things if they are to build new capacity quickly. First, is access to capital. Some of this should come in the form of capital grants to not-for-profits or municipalities or school boards who are willing to move quickly. Some of this can be in the form of low-interest loans, like those that will soon be available from CMHC. Governments should guarantee the loans, but most importantly, the Ontario government needs to ensure that there will be ample operating funding for child care centres to pay back the loans over time.

The second thing that not-for-profits need is a development champion – a development agency that specializes in handling all the details involved in building new capacity or renovating existing capacity. This is familiar territory for co-operative housing or not-for-profit housing developments. There are specialized agencies that handle the housing development and then turn the housing over to co-ops or not-for-profit housing agencies to manage and operate. This should be the case for child care as well.

Neither of these barriers is particularly insurmountable, but they do require governments to facilitate surmounting them. In many cases, public agencies such as municipalities, school boards, and community colleges can help a great deal in supporting not-for-profit and public developments. And the provincial and federal governments should be open to expansions of kindergarten integrated with before-and-after school care.

Ontario shows that rapid expansion of not-for-profit child care services is very possible. Over the 10 years up until 2019-2020, centre spaces increased in Ontario by 198,600. Fully 85% of the increase (168,900 spaces) was in not-for-profit child care.

Quebec shows us the terrible cost of expanding mostly in the for-profit sector

Todd Smith should talk to Mathieu Lacombe, Minister of Families in Quebec from October 2018 to October 2022 in the conservative government of François Legault. Andrew-Gee in the Globe and Mail quotes Mathieu Lacombe: “Allowing for the expansion of private daycare, he said, was the ‘biggest mistake the Quebec government committed in the last 25 years.’”

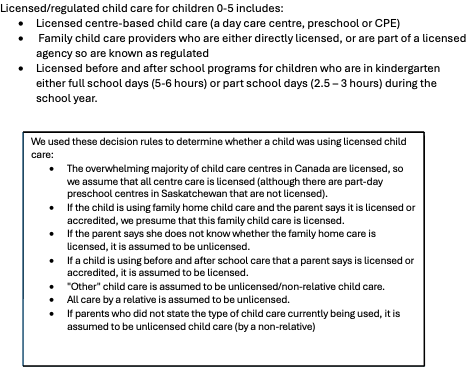

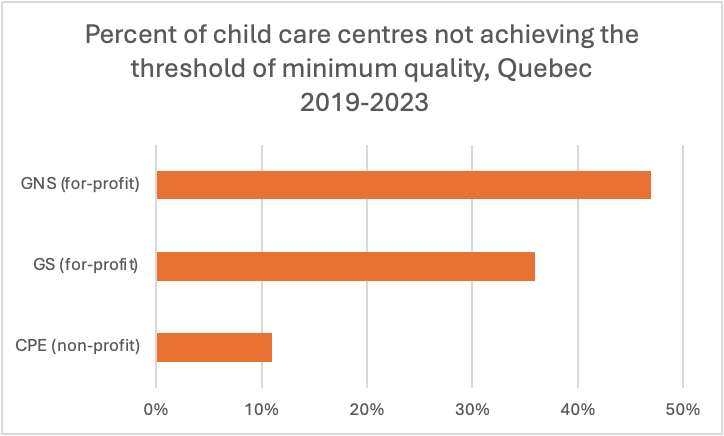

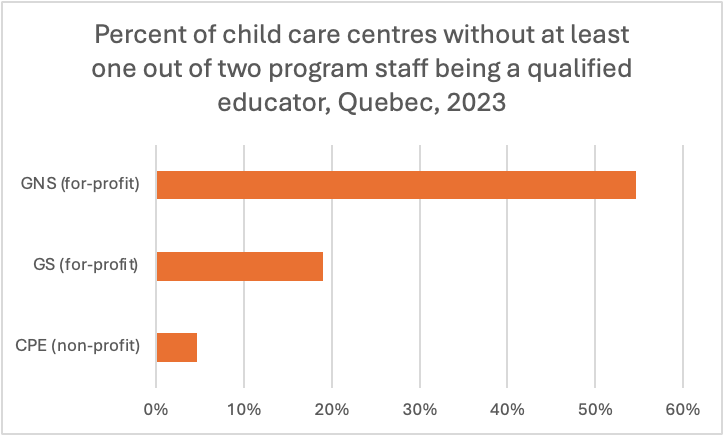

Of course, Todd Smith could also decide to read the Auditor-General’s report for 2023-24 in Quebec. This report looked at measured quality levels in child care centres serving children 3-5 years of age. It also looked at what percent of front-line child care staff are qualified early childhood educators. The Auditor-General investigated the performance of three types of child care centres – the nonprofit CPEs, the for-profit child care centres that charge a fixed fee, and the for-profit child care centres that are funded by a parental tax credit for child care expenses (and do not have fixed fees).

For-profit operators are always looking for a way to save money and increase profits. In child care, saving money generally means cutting back on staffing, because staffing takes up the large majority of the costs of providing care for your children. Before the pandemic, the required ratio in Quebec was that 2/3rds of front-line staff would be qualified staff – early childhood educators with a diploma. This ratio was lowered to 1/3rd of staff during the pandemic as an emergency measure but raised to ½ in March 2023. It was supposed to return to 2/3rds by March 2024, but the Quebec government had to delay this due to widespread shortages of early childhood educators.

The table below gives the full story for 2023 in Quebec. It tells us what percent of the three types of child care centres were below three benchmark levels of child care staffing. The first benchmark is one-third of staff who are qualified as early childhood educators. The second benchmark is one-half and the third benchmark is two-thirds of staff qualified as early childhood educators.

As you can see, the nonprofit centres score much better on the percent of early childhood educators than either of the for-profit categories. Shockingly, 19% of the for-profit tax-credit-funded centres do not even have one out of every three staff qualified as an early childhood educator. Over half of these centres do not meet the currently required ratio of one-half of staff being early childhood educators. And 86% of these for-profits do not meet the 2/3rds requirement that Quebec has been trying to re-establish.

Percent of Front Line Staff Who are Qualified Early Childhood Educators in Non-Profit, For-Profit Fixed Fee, and For-Profit Variable Fee Centres in Quebec, 2023

| % of nonprofit centres | % of for-profit fixed-fee centres | % of for-profit tax-credit-funded centres | % of all centres |

| Less than 1/3rd of staff qualified as educators | 1% | 3% | 19% | 7% |

| Less than 1/2 of staff qualified as educators | 5% | 19% | 55% | 23% |

| Less than 2/3rds of staff qualified as educators | 18% | 53% | 86% | 46% |

Staffing has a big effect on quality, of course. Quebec has had a program of testing quality in 3-5 year-old classrooms in Quebec centres since 2019. The Auditor-General summarized the results. Over the period 2019 to 2023, 36% of “garderies subventionées” – for-profit child care centres that charge a fixed fee – failed the quality examination. In other words, they showed quality levels that had some important problems and were unacceptably low. Worse than that were the “garderies non-subventionées” – the tax-credit-funded child care centres that are able to set their own fee levels and wages. 47% of these – very nearly half of all centres tested – failed the quality examination over the period 2019-2023. In line with their greater reliance on qualified early childhood educators, only 11% of CPEs – the nonprofit child care centres that are the heart of the fixed fee system – failed the quality test.

There is no such thing as a free lunch. Todd Smith should learn that lesson. In the short run, you might save money by relying on for-profit child care expansion, because they will find their own capital money, especially corporate child care with deep pockets and those supported by private equity capital. Pretty soon, however, you will have built a child care system that is offering poor quality services to your province’s children and their parents. And you know that you will end up paying for the for-profit’s capital expansion in the long run, so you might as well do the work now to encourage non-profit and public child care to take up its 70% share.

What we have in Quebec is a demonstration of the pernicious effects of unleashing the profit motive in child care – which is what Quebec did especially from about 2009 onwards. I am not trying to say that all for-profit operators provide poor quality child care or that all of them skimp on child care staffing. Some small for-profit operators provide good quality care and devote themselves to quality improvements. You can have a certain percentage of for-profit providers in a publicly-funded child care system, but there need to be strong measures of public management that limit the ability of for-profit enterprises to extract profit at the expense of quality. The measures of public management are obviously insufficient in parts of Quebec’s child care system. And Todd Smith cannot be trusted to ensure strong public management in Ontario.

Who’s to blame for child care shortages in Ontario? Look in the mirror, Mr Smith.