The Labor federal (i.e., Commonwealth) government of Australia has declared its intention to move towards universal child care. There is a lot of interest in the Quebec model. The Commonwealth government asked the Productivity Commission to investigate and to provide a roadmap towards universal early childhood education and care throughout Australia.

The post below is my submission in response to the draft report of the Productivity Commission which you can find here. As you can see, my advice and comments are strongly informed by Canada and Quebec’s experiences.

Response to the Productivity Commission Draft Report

Main Messages

- The final report of the Productivity Commission should lay out a 10-20 year vision of recommended steps to achieve universal affordable, accessible, high quality child care. The recommendations in the draft report go only\ part way to universal child care. The recommendations should include ways in which there can be guaranteed fee levels for parents, much greater financial accountability of operators, and substantial introduction of supply-side operational funding.

- There should be a much stronger gender equity lens by which recommendations are judged and through which recommendations are presented. This would affect recommendations that imply that 3 days a week is the norm for child care attendance and mothers’ participation in the labour force.

- The commercialization of child care provision should be an issue of concern. Child care growth has been very unbalanced; nearly all new centre-based child care for at least 10 years, and probably 20 years, has been commercial. There are not adequate supports needed for expansion of not-for-profit services.

- In the draft report, the description and lessons learned from the experience of child care reforms in Quebec is one-sided.

There are some good things about the lengthy and detailed Productivity Commission Draft Report.

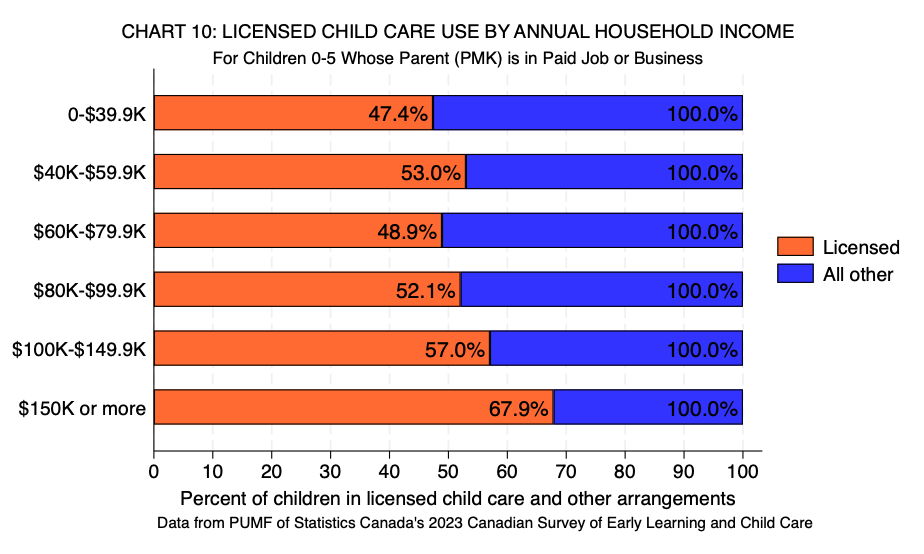

If there is not enough money to do everything right away, it is often sensible to prioritize providing child care services to children in lower-income families. Moving to 100% subsidy and getting rid of the activity requirement for 3 days a week of child care services will address some important barriers to participation by children in lower-income families while directing over half of the additional assistance to families in the lowest 20% of the income distribution. Even here, there are potential issues with the proposals[1].

Getting rid of the activity requirement for 3 days a week will also help some middle-income families where parents have irregular work activity and will tend to normalize regular child care attendance for children.

And the Productivity Commission dips its toe in the water of supply-side funding in remote communities where the profit motive clearly does not adequately encourage needed supply. This is an important start, even if a minor one.

However, as a guide to the pathway to universal child care in Australia, the Productivity Commission’s draft report is disappointing.

- The government asked for a plan to move towards universally accessible, affordable and high-quality child care. This draft report does not deliver this. Instead it chooses to primarily fill one hole in the current state of accessibility – access by lower-income families. Unless the Productivity Commission believes that all other families already had affordable access to child care (which is unlikely since the average out-of-pocket amount that parents pay for centre-based child care is $44.42 a day per child), remedying this one (important) problem will certainly not deliver universal child care. As long as there is no legislative or regulatory limitation on parent fees and no limitation on centres charging full fees for unused hours above 50 in a week, child care in Australia will be unaffordable and inaccessible for some families, perhaps many families, who have middle and higher incomes, as well as families with lower incomes. As long as there are either financial or supply barriers that prevent access, early childhood education and care is not universal. Frankly, despite the Productivity Commission’s mandate to study how universal child care can be achieved, there is evidence in the draft report of some bias against universal child care, reflected in the cautious nature of the recommendations and in the one-sided evaluation of Quebec’s system of universal early childhood services.

2. The Productivity Commission’s draft report appears to reflect a view that child care markets work well in Australia, and that strong competitive pressures already compel commercial operators of early childhood services to keep costs low, expand to serve new needs and continually enhance quality. In other words, the Productivity Commission believes that current funding and regulatory arrangements provide the appropriate incentives and controls to make child care providers serve the public interest. Apparently, only a few tweaks are necessary to make these services more accessible.

This optimistic view is less true than the Productivity Commission believes; the problems are larger and the need for reform is greater. First, we know that competition in child care markets is very localised, largely because few parents want to regularly transport their children more than a couple of kilometres to a child care service. So, each centre only really competes – on price, services and quality – with other centres close by. Generally, that means that competitive pressures are not that strong.

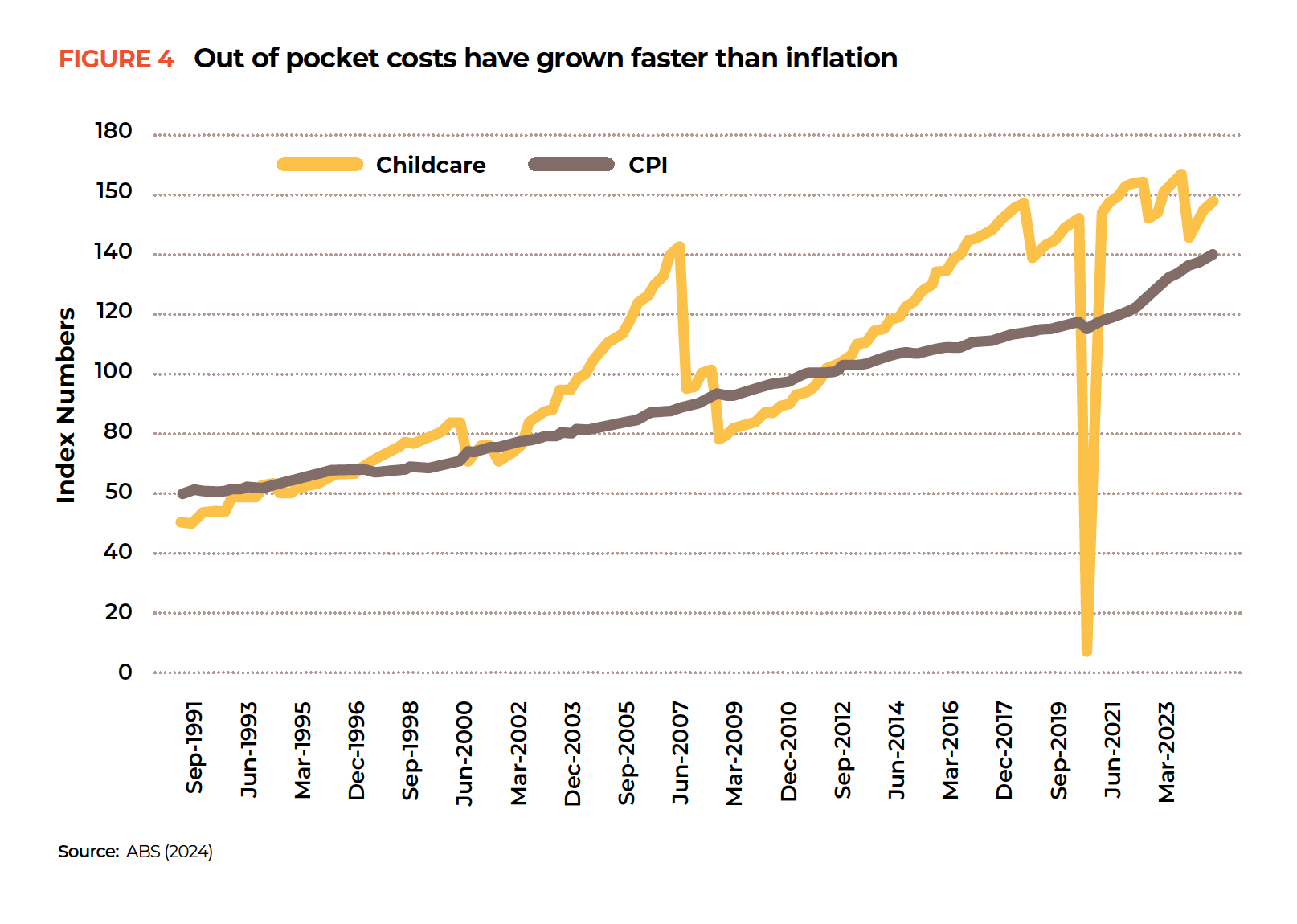

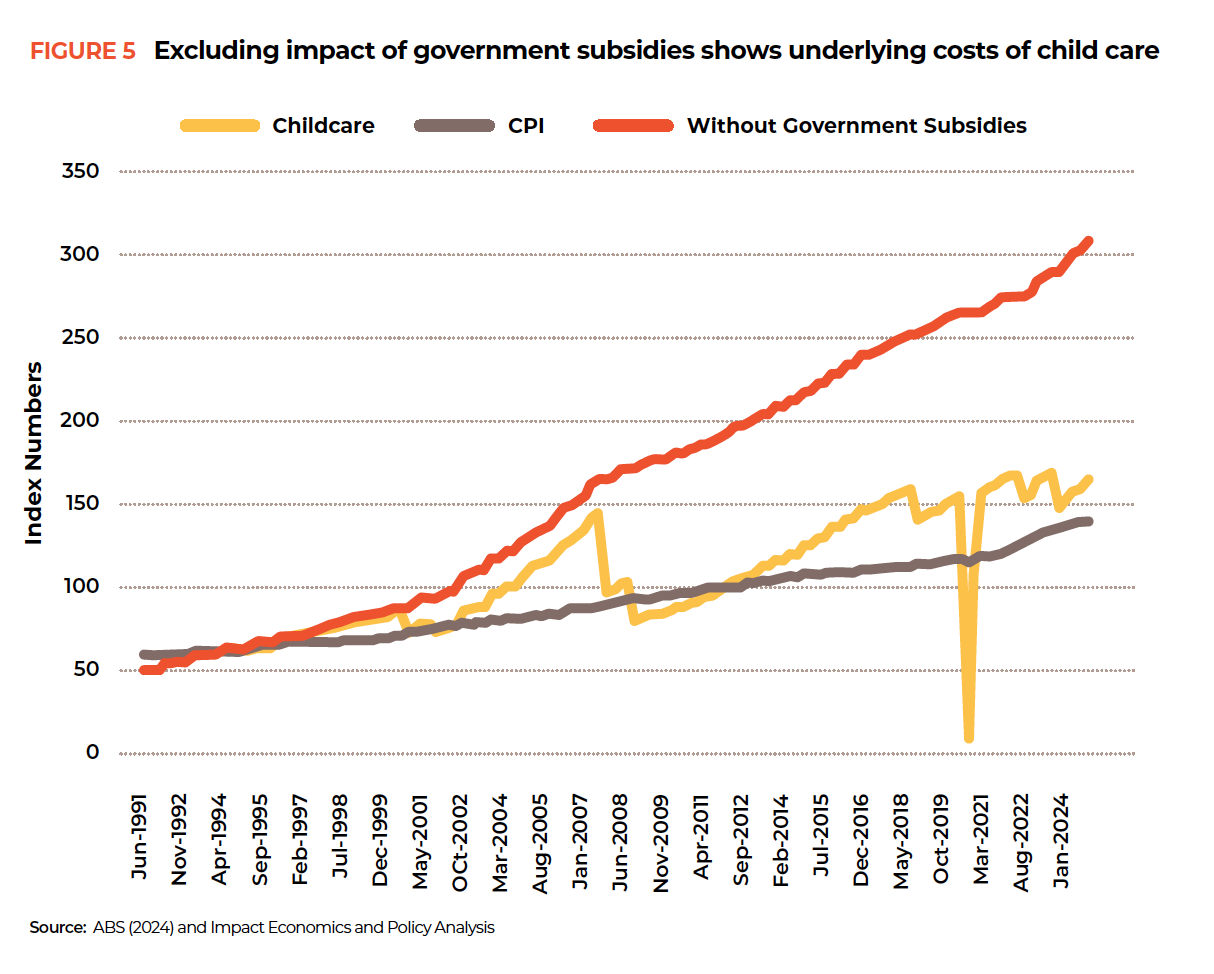

Fees have not been kept down by competition; they have been continually rising for many years. The current average daily fee for centre-based child care is $133.96 per child. Over 20% of child care centres charge more than the hourly rate cap (currently $13.73 per hour for centre-based day care for children younger than school age), particularly for-profit centres. There is little evidence that costs and fees are controlled by strong competitive pressures.

One of the hallmarks of competitive markets is that prices charged are forced down close to actual costs. If the price of one product or service is much higher than its per-unit costs, we would expect profit-seeking producers in a competitive market to offer this product or service at a lower price and take a large number of customers away from existing providers. In centre-based child care, given the required staff-child ratios, the labour costs for infant care must be close to 3 times the labour costs of child care for three- and four-year-old children. And labour costs are the large majority of total costs. Yet, competition does not drive centres to charge much lower fees for older children than they do for infants. There is a large variation in per-child costs and there is virtually no difference in fees. And there are long waiting lists for child care for children less than two years of age, mostly because infant care is less profitable. These facts are a strong signal suggesting that child care markets in Australia are only weakly competitive.

Figure 4 of the interim ACCC report suggests that average occupancy rates of large providers of centre-based day care are about 75%. We know that occupancy rates are a key driver of per-unit costs. In a competitive market, we would expect strong pressures on operators to cut fees in order to increase occupancy, lower per-child costs and maintain quality. This does not appear to be widespread in child care markets.

In short, the main mechanism that makes the Productivity Commission so complacent – competitive pressure – cannot realistically be assumed to deliver publicly beneficial results on its own. There is a need for more public management – active market stewardship – and financial accountability.

3. There is no realistic plan to keep child care fees from rising faster than the CPI (which they have been doing for many years)[2]. Draft recommendation 6.2 suggests a new hourly rate cap for Child Care Subsidy based on the “average efficient costs of providing early childhood education and care services”. Unfortunately, there is no unique average efficient cost. As mentioned above, just think of infant care with required child-staff ratios of 4 to 1 vs. care for children over 36 months of age with required child-staff ratios of 11 to 1 in many states and territories. How could there possibly be a unique average efficient cost per unit across these different age groups? And look at cost variations that are recognized in supply-side-funded jurisdictions. In Quebec and New Zealand[3], for instance, child care operating payments vary across a number of important factors that drive key cost variations – staff experience levels and qualifications and pay rates, legitimate variations in arms-length occupancy costs, higher per-unit costs in thinner markets, etc. Unless the Productivity Commission can propose a realistic set of rate caps tailored to different circumstances and a means of regularly updating them and enforcing them, this recommendation may not work.

4. The recommendations in the report would establish 3 days a week as a norm for the number of days a mother should work. This is negative for gender equity, which is already dramatically impacted by the almost universal assumption that women are primarily or solely responsible for the day-time care of children before school. The draft Productivity Commission report shows that the average size of the motherhood penalty in Australia – the amount of previous earnings that is lost when mothers bear children – is 55% (!), higher than in many other countries. The motherhood penalty is explained by lower rates of employment, lower hours per week of employment, and lower hourly pay of mothers. The Productivity Commission is doing a good thing by reducing the impact of the activity test on access to child care. That will lower barriers to employment for mothers. However, they should recommend its elimination entirely for 5 days a week. To me, the recommendation as it stands suggests that children only need child care for 3 days a week, and that child care for more than 3 days a week may be negative for children and is done only for the mothers who insist on working too long weekly hours (to whom the activity test is applied). There is increasingly strong evidence[4] that universal child care in Quebec and elsewhere has reduced motherhood penalties substantially.

5. The Productivity Commission appears to believe that the widespread use of only three days a week of child care is due to maternal preference rather than to the unaffordability of 5 day a week child care. They show self-reported numbers that allegedly prove that very few mothers would work longer hours each week (and use 5 days of child care) under any circumstances. In other words, the motherhood penalty in Australia is the result of mothers’ deliberate and free choices. I doubt it. In contrast, the ACCC believes that “the price of childcare significantly impacts how much childcare households use.” (p. 22).

It is true that lower labour force participation and part-time work for mothers are strong norms in Australia, compared to many other countries. However, there are reasons to believe that if child care was universally affordable and accessible in Australia, those norms would change. As evidence, look at the very substantial changes in labour force participation of mothers with children 0-4 in Australia over the 12 years from 2009-2021. In 2009, 48% of mothers with young children stayed outside the labour force. By 2021, that number had fallen by one-third (16 percentage points!) to 32%. That would seem to indicate that mothers’ employment decisions may be quite sensitive to changes in policy, rather than fixed by historical norms. This matters for the motherhood penalty, but it also matters a lot for the funding of child care programs; in Quebec, a large portion of the fiscal costs of child care programs is funded by increased incomes and taxes due to changed employment.

6. There is no plan for requiring financial accountability of providers for the vast sums of government money they receive. The legal fiction is that parents who receive subsidies for the purchase of child care are effective watchdogs of how the money is spent. This is so obviously not true that it needs little argument to reject it. But, there is no requirement for providers to show that they have spent money wisely to achieve publicly desirable purposes. There are some serious red flags that the Productivity Commission does not really address. They report that there are many hours of ECEC services that are paid for each day (by parents and the government) but are not used. This sounds like evidence of substantial inefficiency in current funding and attendance arrangements. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) report concludes that for-profit child care providers pay more for occupancy costs than not-for-profit providers (and that part of this may be due to the use of facilities for which ownership is not at arms-length)[5]. Further, for-profit services are found by the ACCC to be of worse average quality[6] than that provided by not-for-profit providers. The Productivity Commission should be making recommendations about compulsory and regular financial accountability. I believe that, in Australia as in Canada, child care is fundamentally a public service (with about 80% of costs paid by the public purse) but one that is delivered by private operators. Detailed and regular reporting on how public moneys are spent should be an obvious requirement.

7. The final report of the Productivity Commission should lay out a 10- to 20-year vision for the establishment of universal child care services in Australia. The recommended National Partnership Agreement would be a part of this plan. Wrap-around child care for preschools would be a part of this plan. The expansion of supply-side funding of services with fees controlled would be part of this plan. The new independent ECEC Commission would monitor and report on progress towards universal access and make ongoing recommendations to move towards it. The Productivity Commission hints at a long-term vision but is not explicit. This allows the Productivity Commission to duck a lot of longer-term questions about affordability, commercialization of the system, financial accountability, and generally the evolution towards serving public interests better.

8. Australia has a long-established demand-side (voucher) funding system for child care. It allows providers to set their own fees, decide on staff compensation conditional on meeting the award levels set by the Fair Work Commission, choose the children and parents they will serve from those who apply and choose the hours of service to provide. This is not, in my opinion, the best system going forward; I believe that a system of supply-side-funded services with a guaranteed set fee level (plus fees reduced below the set-fee level or to zero for some families) would be better. However, changing funding systems is not easy and there is often a lot of push-back from those in the system. Why not think outside the box? Why not establish an alternative supply-side funding system that would exist in parallel with the existing demand-side funding system with incentives for centres to switch?

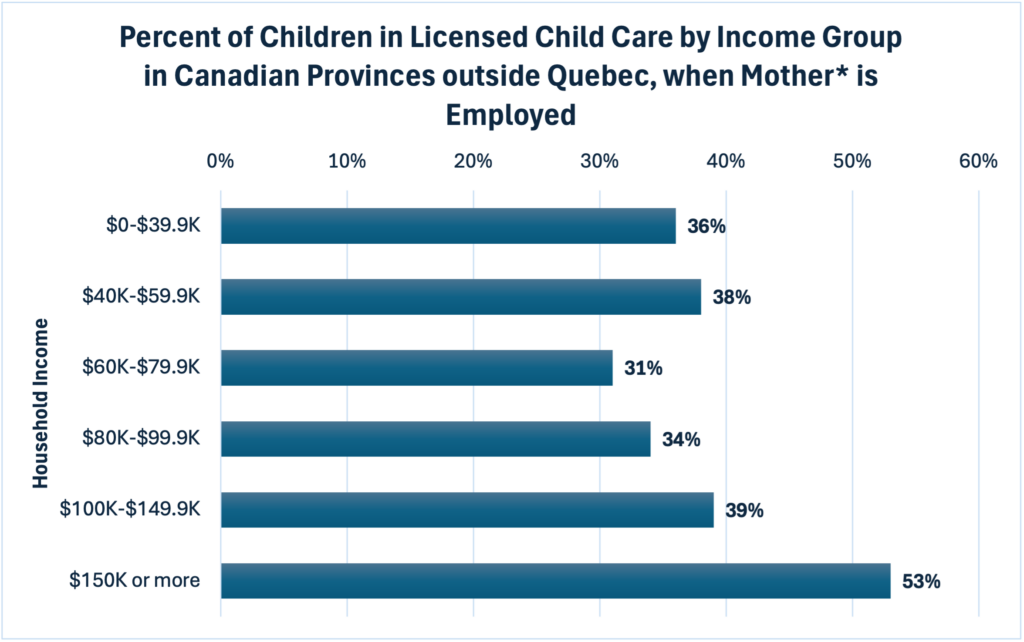

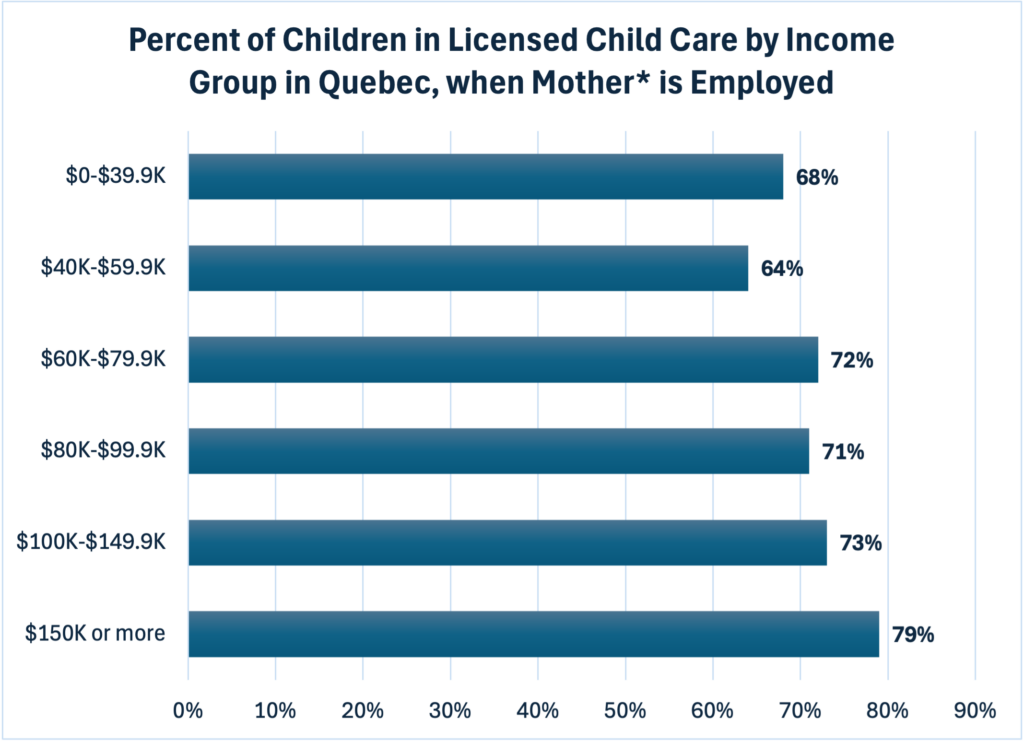

Centres that were funded on the supply-side would have a fixed fee, and enhanced regulatory requirements. In exchange, they would have guaranteed funding to cover costs above parent fees. Set-fees that are known and predictable are very popular with parents at all income levels and, in Quebec, have encouraged high child care participation by children in lower-income families. There would be strong elements of financial accountability and reporting by centres, requirements to pay above-award wages, reduced ability to rely on part-time and casual staff and other requirements related to quality of care, but some centres and some parents would prefer this. There would be obvious transition difficulties, but this kind of recommendation would boldly look towards transforming Australia’s system into a universal and affordable one.

9. The Productivity Commission does not address the increasing commercialization of child care services in Australia. Virtually all of the expansion of centre-based child care services (not preschools) in the last decade – a 50% increase in the number of spaces available – has been in the for-profit sector. As the ACCC interim report notes: “the child care sector is widely viewed as a safe and strong investment with guaranteed returns, backed by a government safety net.” The Productivity Commission report does not even raise the question of whether this extremely unbalanced growth pattern is desirable. The growth in services that has occurred is disproportionately located where returns are higher, rather than where need is greater, as shown in Figures 3 and 7 of the draft report. 1% of providers now provide 35% of all centre-based child care services. The Productivity Commission should be making recommendations about means of encouraging growth in not-for-profit and public provision of services. These recommendations would call for planned development and dedicated loan guarantees or other capital funding targeted at not-for-profit providers. I believe that Australian children and families are unlikely to prefer a universal child care system with unplanned expansion and complete domination of service provision by commercial incentives and ethics.

10. The Productivity Commission draft report provides a one-sided summary of the experience and effects of Quebec’s universal child care system. Although it is true that economic researchers found short-run negative effects on some children (effects were found to vary substantially across different child groups[7]), the most recent and comprehensive work on Quebec, using a triple-difference estimator similar to other studies (Montpetit et al., 2024[8]) does not find any long-run negative effects on children’s completed education. Rather, they find that the long-run education levels of Quebec children who had been eligible for $5 a day child care were no different than their peers in other parts of Canada. In particular they write: “We find no evidence of negative effects on educational attainment of eligible children in the long-run. This pattern is true for each educational level, namely for university, high school, and college completion….

The results suggest a positive but statistically insignificant impact on completion of a university degree, the most comparable outcome across provinces, and no impact at lower levels.”(p. 21). Further, Montpetit’s study calculates the social cost of increased “youth criminal activity” identified by Baker, Gruber and Milligan (2019[9]) and finds negligible social costs because the identified transgressions were minor.

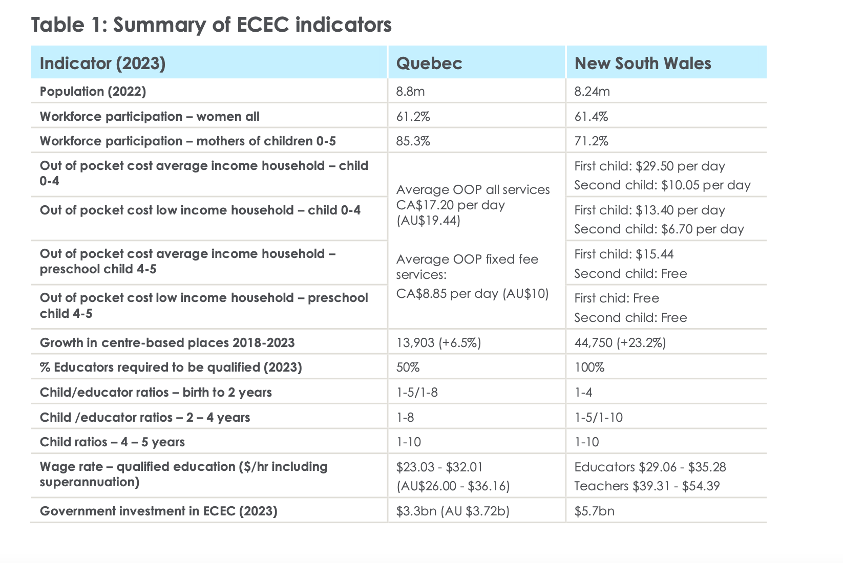

11. The Productivity Commission draft report gives little sense that this fixed-parent-fee child care program is an incredibly popular social program with Quebec parents. The reader will struggle to understand why the Canadian federal government decided in 2021 to spend $30 billion over 5 years to spread the Quebec child care model of a fixed-fee, supply-side-funded program across the country. The reader of the draft report will not be told that Quebec’s child care reforms had sufficient impacts on mothers’ employment and economic growth to more than pay for the costs of the program according to the influential opinion of prominent Canadian economists (Fortin, Godbout, St. Cerny, 2013[10]). Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008[11]) find that Quebec’s policy reforms increased labour force participation of mothers with children 0-4 by 7.6 percentage points from 61.4% before the policy. They estimate the labour force elasticity to child care price to be 0.25. In addition the child care reforms increased the annual hours worked, weeks worked and earnings; these elasticities were 0.26, 0.28, and 0.34, respectively. With these elasticities, a 10% decrease in the fee would increase annual hours worked by 2.6%, increase weeks worked by 2.8% or increase earnings by 3.4% on average.

Lefebvre, Merrigan and Verstraete (2009[12]) found that the labour force impacts lasted beyond the preschool child care years when mothers no longer had any children 0-5 years of age, and that the positive labour force impacts were particularly strong amongst mothers with lower levels of education. Even if long run labour force effects are ignored, the recent study by Montpetit and colleagues (2024) finds that the overall benefits of universal child care in Quebec are three and a half times the costs. This includes a careful evaluation of the value of the improvements in the well-being of Quebec mothers from universal child care services.

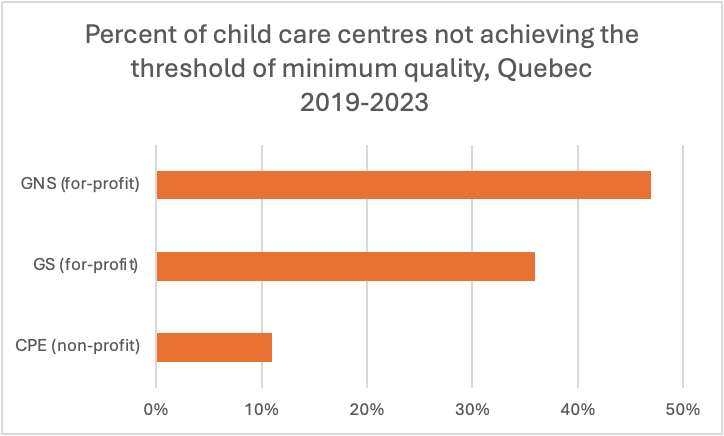

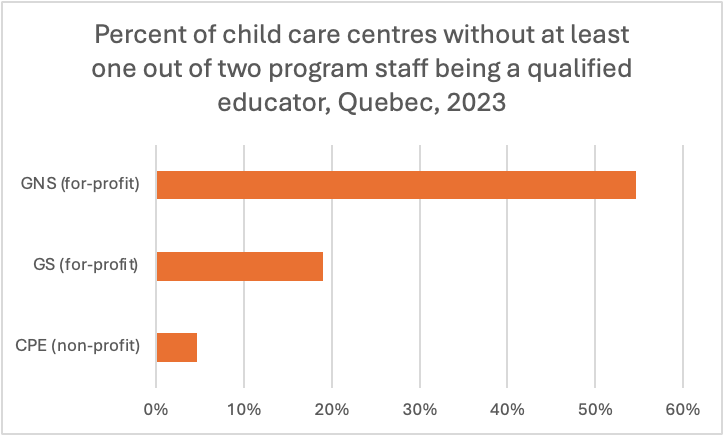

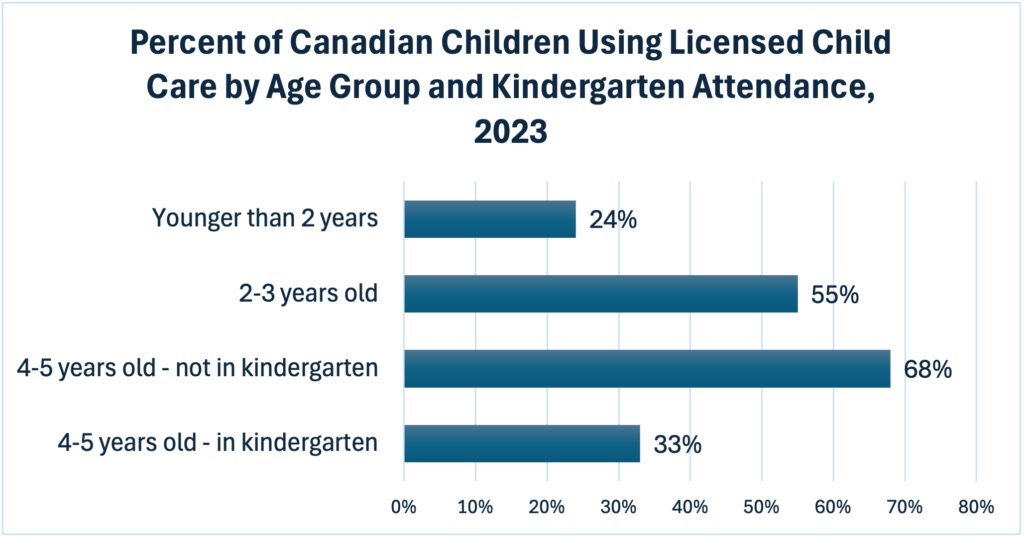

12. The Quebec model of funding and management of child care services is not a perfect one. Two factors made its birth particularly difficult. First, when they initiated the $5 a day program, Quebec only had enough child care supply to provide services to 15% of the child population 0-4 years. For 20 years, they scrambled to increase supply and have now reached nearly 70%. However, this scramble to increase supply meant relying too heavily on both family child care and for-profit child care with weaker regulation. These types of care have been the Achilles heel of quality[13] in the Quebec system, a problem that is now being addressed. Second, this was a program funded exclusively by the provincial government; at that time, the federal government was unwilling to provide any financial support. The provincial governments in Canada have modest taxing powers, so services were not as generously funded as they should have been. With the federal government coming to the table in 2021 with billions of dollars of additional funding, child care services in Quebec will now be funded more appropriately. I have described the problems of the Quebec model of child care here[14], warts and all. However, these problems are not inherent in a universal program; Australia already has a large child care supply and substantial financial resources available to support good quality programming. It can gain the substantial benefits of Quebec’s universal program without the birth pangs that Quebec has faced.

Commentators have noted that low-income families in Quebec do not have as much access to good quality child care as do middle income families. That is true and is a problem. As far as I can tell, that is true and is a problem in most countries whether child care systems are universal or not; it is certainly true in Australia[15]. However under Quebec’s universal program it is also true that a much higher percentage of low-income families were able to access licensed child care than was the case with the targeted funding that predominated in the rest of Canada[16]. Children from low-income families also were particularly likely to benefit from their access to early childhood programs[17].

13. The terms of reference of the Productivity Commission enquiry require that it study “the operation and adequacy of the market, including types of care and the roles of for-profit and not-for-profit providers, and the appropriate role for government.” Further, these terms of reference direct that “The Commission should have regard to any findings from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s Price Inquiry into child care prices….” However, the findings in the ACCC draft report about the child care industry scarcely get any mention, including differences in costs and priorities of for-profit and not-for-profit providers. The ACCC report provides important insights about costs and performance not available elsewhere.

14. I hope that many of these issues will be addressed directly in the final report of the Productivity Commission.

Gordon Cleveland, Ph.D.,

Associate Professor of Economics Emeritus,

Department of Management,

University of Toronto Scarborough

FOOTNOTES/ENDNOTES

[1] These policy changes -removing activity requirements for 3 day attendance and 100% subsidy up to $80,000 -should mean many more lower-income families wanting access to child care. Some operators prefer to serve a more exclusive clientele; this is known as creaming. Under current rules, centres that charge a fee that is above the maximum hourly-fee limit are likely to effectively exclude most of these children. Perhaps the Productivity Commission should require that centres be compelled to serve these children at the maximum hourly fee if parents apply to attend.

[2] The cost of child care in Australia is pretty high. Centre-based child care fees per hour (averaged across ages 0-5) were $11.72 in 2022. The Productivity Commission reports that the average daily fee is $124 per day. From 2018 to 2022, gross fees in Australia increased by 20.6% in comparison to the OECD average of 9.5%. The OECD ranks Australia as 26th out of 32 countries on affordability of child care for a typical couple family with two children. This is despite the Australian Government contribution to fees being significantly higher than most other OECD countries – 16% in Australia compared to the OECD average of 7%.

[3] See https://childcarepolicy.net/cost-controls-and-supply-side-funding-what-does-quebec-do/ for a discussion of details of child care funding in Quebec and see https://childcarepolicy.net/new-zealands-funding-system-for-early-childhood-education-and-care-services/ for a discussion of details of child care funding in New Zealand.

[4] See Connolly, M., Mélanie-Fontaine, M. & Haeck, C. (2023). Child Penalties in Canada. Canadian Public Policy doi:10.3138/cpp.2023-015. See also Karademir, S., J.-W. Laliberté, and S. Staubli. (2023). “The Multigenerational Impact of Children and Childcare Policies.” IZA Discussion Papers No. 15894, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Germany. As Karademir et al indicate “The disproportionate impact of children on women’s earnings constitutes the primary factor contributing to persistent gender inequality in many countries.”

[5] Land and occupancy costs are about 18% of the total of all costs for large for-profit providers compared to about 10% for large not-for-profit providers. This is not due to what the Aussies call “peppercorn rents” (i.e., below-market rents provided on a goodwill basis). The average profit margin for large centre based day care providers was about 9% for for-profit providers and about 6% for not-for- profit providers in 2022.

[6] About 95% of the staff in not-for-profit centres are paid “above-award” compared to 64% in for-profit centres. Not-for-profit providers are much more likely to hire their staff on a full-time basis, whereas for-profit providers primarily rely on part-time staff. As the ACCC report suggests: “large not-for-profit centre-based day care providers invest savings from lower land costs into labour costs, to improve the quality of their services and their ability to compete in their relevant markets.” The ACCC finds that centre-based day care services with a higher proportion of staff paid above award and with lower staff turnover have a higher quality rating under the National Quality Standard.

[7] Kottelenberg and Lehrer provide evidence of substantial heterogeneity in the impacts of the Quebec child care reforms by the age of the child, the child’s gender and by initial abilities in a series of studies published in 2013, 2014, 2017 and 2018. Kottelenberg, M. J. and Lehrer, S. F. (2013). New evidence on the impacts of access to and attending universal child-care in Canada. Canadian Public Policy, 39(2):263–286. Kottelenberg, M. J. and Lehrer, S. F. (2014). Do the perils of universal childcare depend on the child’s age? CESifo Economic Studies, 60(2):338–365. Kottelenberg, M. J. and Lehrer, S. F. (2017). Targeted or universal coverage? assessing heterogeneity in the effects of universal child care. Journal of Labor Economics, 35(3):609–653. Kottelenberg, M. J. and Lehrer, S. F. (2018). Does Quebec’s subsidized child care policy give boys and girls an equal start? Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’ ́economique, 51(2):627–659. Kottelenberg and Lehrer (2017) finds that levels and changes in home learning environments by some parents in response to the Quebec reforms were an important explanatory factor of differential effects on children.

[8] Montpetit, S., Beauregard, P., & Carrer, L. (2024). A Welfare Analysis of Universal Childcare: Lessons From a Canadian Reformhttps://drive.google.com/file/d/1dDWvj2e08YodXAWd5zdmBKP3j-kxt1Uj/view

[9] Baker M., Gruber J., & Milligan K. (2019). The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Program American Economic Journal. Economic Policy, Vol.11 (3), p.1-26; American Economic Association.

[10] Fortin, P., Godbout, L. and St.Cerny, S.. (2013). “Impacts of Quebec’s Universal Low-fee Childcare Program on Female Labour Force Participation, Domestic Income and Government Budgets. University of Toronto. Toronto, ON. Translated from French https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/home/sites/default/files/2024-02/impact-of-quebec-s-universal-low-fee-childcare-program-on-female-labour-force-participation.pdf Original reference is Fortin, P., Godbout, L., and St-Cerny, S. (2013). L’impact des services de garde a contribution reduite du quebec sur le taux d’activite feminin, le revenu interieur et les budgets gouvernementaux. Revue Interventions economiques. Papers in Political Economy, 47.

[11] Lefebvre, P., Merrigan, P. (2008). Childcare policy and the labor supply of mothers with young children: a natural experiment from Canada. Journal of Labor Economics 23, 519–548.

[12] Lefebvre, P., Merrigan, P., Verstraete, M. (2009) Dynamic Labour Supply Effects of Childcare Subsidies: Evidence from a Canadian Natural Experiment on Low-fee Universal Child Care. Labour Economics 16: 490-502.

[13] Couillard, K. (2018) Early Childhood: The Quality of Educational Childcare Services in Quebec. Observatoire des tout-petits. Montreal, Quebec, Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon. Page 25 of this document charts the measured quality differences between CPEs (not-for-profit centres) and the for-profit non-subsidized daycares. In the CPEs that are the heart of the supply-side funded system, in two age categories, 4% or fewer of centre rooms are of poor quality. In the for-profit child care centres funded by demand-side tax credits to quickly boost supply, 36%-41% are of poor quality.

[14] Cleveland, G., Mathieu, S., and Japel, C. (2021) What is “the Quebec Model” of Early Learning and Child Care? Policy Options, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal QC. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/february-2021/what-is-the-quebec-model-of-early-learning-and-child-care/#:~:text=The%20plan%20in%20Quebec%20was,educational%20child%20care%20after%20that.

[15] See Cloney, D., Cleveland, G., Hattie, J., and Tayler, C. (2016) Variations in the Availability and Quality of Early Childhood Education and Care by Socioeconomic Status of Neighborhoods Early Education and Development Vol. 27(3 ):384 – 401, and also see : Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) (2020) Quality ratings by socio-economic status of areas, ACECQA, Sydney

[16] Cleveland, G. (2017) “What is the Role of Early Childhood Education and Care in an Equality Agenda?” pp. 75-98 in Robert J. Brym ed. Income Inequality and the Future of Canadian Society ISBN-13:978-1-77244-044-7 Oakville, ON: Rock’s Mills Press. Proceedings of the inaugural S.D.Clark memorial symposium.

[17] Kottelenberg and Lehrer (2017) op. cit.